Arrowmont Welcomes Bio Artist Maria Schechter’s Mycelium Sculpture The Gatekeepers to Campus

January 24, 2024

Arrowmont Welcomes Bio Artist Maria Schechter’s Mycelium Sculpture The Gatekeepers to Campus

By Megan Adams & Maria Schechter

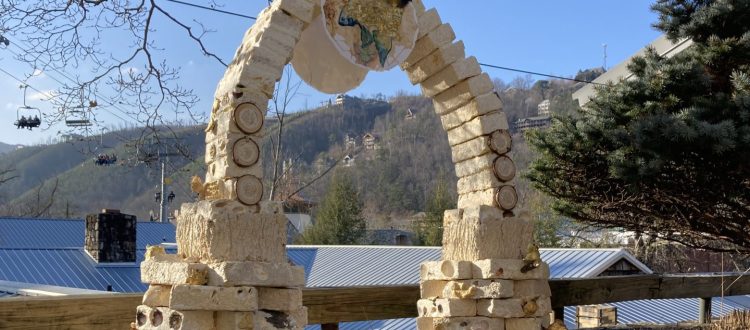

Maria Schechter’s The Gatekeepers now on view on Arrowmont’s library terrace.

Maria Schechter’s The Gatekeepers finds a new home on campus at Arrowmont School of Arts and Crafts. After exhibiting her sculpture in Arrowmont’s 2023 national juried exhibition Degrees of Commitment: Climate, Ecosystems, and Society, Schechter offered her piece to Arrowmont to be displayed outdoors among our other outdoor art. As the new stewards of this work, Arrowmont will be documenting the changing sculpture as it decomposes over time and the environmental materials return to the earth. To learn more about the process, materials, and inspiration behind the piece Arrowmont’s 2023-2024 Kenneth R Trapp Craft Assistant/Curatorial Fellow Megan Adams interviews artist Maria Schechter.

As an artist you are working in a very interdisciplinary way, your practice bridging art, science, environmentalism, and spirituality. You describe yourself as a bio artist. This environmentally engaged way of making art in conjunction with naturally occurring biological processes is slowly but surely gaining some momentum around the world, but because of it pushes categorial boundaries, bio art hasn’t always been legible to the mainstream art world or to those who aren’t as familiar art that adopts techniques, approaches, and material from other disciplines. Can you explain what it means to be a bio artist and perhaps share how you found your way to this type of artmaking?

Artists throughout history have had a direct impact on how the world experiences itself. As a bio artist in this century, I believe we carry a responsibility to our materials as well as the communities we serve and the narrative we create. The responsibility lives in the art of communication. We are similar to scientists: We want to visualize what cannot be seen and share what that means for us. I share my bits of my research in both my work and my workshops. However, I am not a scientist. I entered this space only five years ago. My thoughts, intentions, and processes live in a space of spirit or energy. I currently have a bio painting titled The Interior Life of a Mermaid at the Minnetrista Museum and Gardens through February, part of a larger exhibition Open Space: Art About the Land.

Maria Schechter, Interior Life of a Mermaid, 2022. Amaranth clay, cockscomb, copper wire, gold ribbon, gold leaf hieroglyph, mycelium, moss, polymer skin, preserved flowers, pussy willow, recycled plastic, color made of blueberries, Japanese Maple resin, and indigo, seashells and water jewel on watercolor paper. 24in. x 36in. x 3in. Image courtesy of the artist.

The sculptural pieces were grown from mycelium. The colors were made by processing indigo into a dye. I foraged Japanese Maple resin as a highlight in the piece to directly speak to the topic. In relation to the land and what trees give us: food, shelter, medicine, clean air, and trees who store greenhouse gases that are a cause for climate changes. In addition, scientific studies have shown that forest bathing helps humans to bring down levels of depression and anxiety. Bio art is challenging for the art market and arts administrators, such as curators of museums and gallery administration. Articulating the experience of working with mycelium is difficult because it’s as close to Spirit as I can get as a human. Further, it is a challenge to visually articulate what is not seen. I feel the same about forests, animals, and all sentient beings. It is a challenge to reach into a space not many have traveled before. As a bio artist, I encourage other artists and my community to innovate with me. If we can overcome eco-grief together by exploring other materials, it is one way we can address our climate crises. For me, bio art is my way of combating eco-grief, a term coined by Jane Goodall in her new book Hope. Our responsibility as artists is to create works that are approachable. My goal is to inspire others to use healthier materials for a healthier world. If a viewer does not understand my work, it would fall on me to articulate my goals. I found my way to the underground via a scholarship I received from The Fantastic Fungi Global Summit in 2021. An introduction to mycelium should go hand-and-hand with this material provided to me during the Fantastic Fungi Global Summit. The Summit was saturated with authors, leaders, scientists, mycologists, and biologists, such as Michael Pollan and Andrew Weil. I discovered the film Fantastic Fungi by Louie Schwartzberg during recovery from surgery after being in a car accident initiated by an impaired driver. I was hit by 4 other vehicles including the impaired driver and my air bag never deployed. The experience left me with a traumatic brain injury. In addition, I would never be able to use my arms and hands the way I had in the past, so I needed a new way to express my artistic aspirations. After the car accident in 2018, I spent the first two years moving through surgeries, healing, meditation, research, and recovery. I am just now getting to my spine. For example, I recently had to get a shot in my spine to put off surgery so I can use my right arm to complete my new body of work, which will open in Spring 2024 at the Waldron Center for the Arts in Bloomington, Indiana. I am an artist with disabilities. Once you have a traumatic brain injury, you never return to your fully realized academic self; however, the experience has been pivotal to me having an environmental awakening. After over twenty years of working in oils, I was searching for a new medium that didn’t further challenge my arms and hands. My website is called T6DH, which references The 6 Directions of Healing. Healing myself with the same materials I now use in my artwork feels whole and complete. This is a sacred practice and my greatest joy. I am always ready to talk about the amazing finds by my favorite mycologists: Paul Stamets, who I met at Burning Man, and Merlin Sheldrake, whose book Entangled Life is filled with mycelia majesty and mystery. Notes, Post-its, and reminders highlight my copy of his Merlin’s book, and it helps me to reference the juicy bits I often share in my workshops and environmental talks.

The media line for The Gatekeepers reads “142 mycelium bricks, 2,592 grow hours, 260 lbs. of mycelium, over 2,000 seashells, 32 foraged mushrooms in gold leaf, precious gems, children’s toys, amethyst necklace.” This media line attests to the unique nature of this artwork, from your innovative process and materials to the hours of labor it took to achieve this monument to sustainability and human-environmental harmony. How did the idea for this artwork come about and what was the process you underwent to create The Gatekeepers?

The Gatekeepers took three years to grow. I created it with the intention of inspiring future gatekeepers, specifically youth, to step up and champion security for our sky, ocean, land, and animals. It’s a big ask, but if we don’t start sharing STEM objectives, there will be no earth left. My goal was to make the archway large enough for a child to walk through. Because I was making it for a specific demographic, this naturally formed my guidelines. With a childlike mind, I attempted to create a structure I would like to investigate and understand. To draw sustained curiosity, I chose keystone species so that during any type of educational workshop, I would be able to tell the story of the unseen symbiotic relationships between soil and plants and plants and animals and how their well-being is reliant on us to also be healthy. The structure was grown into the shape of an archway or transitional space. It is the promise of truth and in that truth, we experience life, and we find the answers we have been searching for. Historically arches were used to illuminate triumphs. In this century, it is used to cross over to making a commitment to serve the natural world. To become the next gatekeeper or guardian of our Earth.

I am struck by the way in which you make mycelium, a natural substance that is typically invisible to most humans, visible through this piece. Mycelium is a network of fungal threads (hyphae) that are often found underground in soil or in above ground areas that are quite inconspicuous to the unobservant eye. What can we learn from mycelium? As an artist what lessons have you learned through working with mycelium as your medium?

You can make your own mycelium, but lacking a lab, I purchased my mycelium from Ecovative. Their technology is incredible. The AirMycelium Technology they have created replaces plastics, leather, meat, and other unsustainable industrial products and factory farming with mycelium. As Ecovative says “Their mycelium foundry draws from a world-class biological library and uses a first-of-its-kind, high-throughput testing system to tune and amplify the natural properties of different mushroom strains for a variety of unique material applications at scale.” These guys are epic mycelium whisperers. We can all consider Ecovative a brand, like Windsor & Newton or Van Gogh oil paints. Sculptors who use clay and many painters don’t make their mediums, they buy their materials. I buy unseeded mycelium from Ecovative. The two scientists found a way to take the spores out of the substrate, meaning the material will not fruit mushrooms as mycelium does in nature. I prefer to grow my own mushrooms. This gives me control over shaping my mushrooms, and I have developed experiments to grow mushrooms around seashells. Fungi are allies in so many incredibly unique ways. In the 21st century, bio artists depend on innovators like Ecovative. On the other hand, scientists and physicists look to artists and their rearticulation of their findings and materials. I developed an entire body of work based on a finding from the American Mycologist, Paul Stamets book Mycelium Running. He documents the world’s first underwater gilled fungi, Psathyrella aquatica. My body of work is called Mushroom Aquatic. After the Fantastic Fungi Global Summit, I contacted Ecovative and asked for a donation to grow my first sculpture, The Well Within.

Maria Schechter, The Well Within, 2021. Grown from unseeded mycelium over 23 days (554 grow hours). Contains 43 bricks, 9 panels, and numerous species of seashells. 27in. x 22in. Image courtesy of the artist.

This was the first time I worked with the material. The project was to remind my community, at that time, Central California, that every civilization has had to rebuild, brick by brick. This was after the 2021 Caldor wildfire in El Dorado County, California. I lost my paintings in that fire but felt a deep sense that hope was on the horizon. By tuning into Paul Stamets’ findings on the use of mycelium to develop myco-remediation. This process cleans soil and water via mycelium. Through using mycelium, I learned and now teach the lifecycle of fungi, how related we are as we share 50% of our DNA with the mycelium, and the hyphae threads of fungi have rods and cones like we do in our eyes. The hypha threads have very few rods and cones so they can only see the color red. The main teaching of mycelium is that we are all connected, and we all have the ability to heal ourselves and each other.

Images illustrating mycelium as medium, the process, and Schechter’s lab. Image courtesy of the artist.

This mycelium masterpiece is rich in embedded symbolism from the overall arch/gateway shape to the seashells and smaller reliefs representing natural forms such as bees, moths, and honeycombs as well as several keystone animal species. How do the various elements support the overall message you aim to communicate through The Gatekeepers?

The elements grown into the mycelium of the Gatekeepers project highlight the delicacy of biodiversity and tells the story of how ecosystems rely on the smallest living creatures to the largest living creature on Earth. Approximately 90% of the plants we see, including trees, rely on mycorrhizal fungi. Without mycelium, we would not have trees or plants and that includes our food sources. Without bees, who feed on mycelium and pollinate our flowers and beds of food, humanity is doomed. Every creature plays a role in the cycle of life. If we learn to cultivate our gifts, we can serve our communities and champion food disparities and divisions between people and cultures. I agree with Paul Stamets that if we can wake up enough people to help with this process of healing the planet, then mycelium will save the planet.

Maria Schechter, The Gatekeepers (details), 2022. 142 mycelium bricks, 2,592 grow hours, 260 lbs. of mycelium, over 2,000 seashells, 32 foraged mushrooms in gold leaf, precious gems, children’s toys, amethyst necklace. Images courtesy of the artist.

What led you to choose Arrowmont as the final home and steward for The Gatekeepers?

I was given funding from the Tennessee Arts Commission through another organization to complete the structure. Originally, I was going to show Gatekeepers with an organization outside of Knoxville. My project was not able to be shown with the organization due to programming and timelines. I felt it was right that it stays in Tennessee to serve the public. I did research for arts organizations in the area and found Arrowmont, which led to me to submitting my work for consideration in the nationally juried exhibition: Degrees of Commitment: Climate, Ecosystems, and Society. Every piece I make, I put my heart and soul into. I felt that I learned what southern hospitality means when I met Heather Wetzel and her curatorial team. I have never worked with such warm, kind-hearted, and knowledgeable folks since graduate school at NYU and Schiller in Heidelberg, Germany. When I first met Heather and gave her a big bear hug, I knew this was the right place for my work. I love people! In my work, anyone can feel at home because I know that we are all kin and connected at our roots.

Maria Schechter’s The Gatekeepers on view in Degrees of Commitment: Climate, Ecosystems, and Society in the Sandra J. Blain Galleries at Arrowmont School of Arts and Crafts, September 5-December 16, 2023. Image courtesy of the artist.

In opting to display this artwork outside on campus at Arrowmont in perpetuity you are embracing the inherent ephemerality of this piece, removing it from an indoor gallery space to expose it to the unpredictability of the outdoors from inclement weather conditions to campus critters. What does it mean to you to re-articulate this eco artwork for an environmental context?

This is the final stage of the project. Not that all of my work should go back to the land, but it is an inaugural acknowledgment to my first structure. The piece will be complete when it goes back into the earth. Just as we all will someday. As a practicing Buddhist for the last 30 years, I understand that it is a part of our lifecycle to birth, live, and die. Decomposition is the natural process of life. As artists, we like to think that our work will live on forever, but especially with bio art, the process and acceptance of the transitory nature of the world is embracing the truth that we are in constant motion, constantly changing and so it is symbolic of our lifecycle and of this project.

What do you envision the legacy of this piece to be?

Someday, You and I will be an ancestor. As I write down the new, fascinating findings of mycologists and other scientists, I understand someday, someone may pick up my journal and improve on processes and keep moving forward towards a healthy future. My hope is to inspire others to open up to challenging our climate crises by developing works that will also serve our planet and its people. The critical part is to watch the piece go back into the earth, which will mean that I have developed, created, manifested into our reality this archway, a triumph to serve humankind and earth. Its emphasis is the cycle of life. The legacy is what others choose to do with the wisdom I unearth during my time here on our planet. There are others like me out there co-creating with mycelium. If we keep innovating with this material, we are going to crack the code. Just as roots turn into worlds under a microscope, I often wonder how much we are missing living atop soil. There is still so much to observe and learn.

Megan Adams is an art historian, curator, and community-engaged scholar from Denver, CO. She holds a BA in English from Oklahoma State University and an MA in Art History and Museum Studies from the University of Denver. Adams adopts interdisciplinary approaches to art scholarship and is passionate about studying the relationships between humans and the environment articulated in art throughout time, with a special emphasis on contemporary ecological and environmental art. She has five years of experience doing curatorial and collections work at art museums and non-profit organizations including Hampden Art Study Center, Madden Museum of Art, Denver Botanic Gardens, Colby College Museum of Art, and Arrowmont School of Arts and Crafts. Adams is the 2023-2024 Kenneth R Trapp Craft Assistant/ Curatorial Fellow at Arrowmont School of Arts and Crafts.

Megan Adams is an art historian, curator, and community-engaged scholar from Denver, CO. She holds a BA in English from Oklahoma State University and an MA in Art History and Museum Studies from the University of Denver. Adams adopts interdisciplinary approaches to art scholarship and is passionate about studying the relationships between humans and the environment articulated in art throughout time, with a special emphasis on contemporary ecological and environmental art. She has five years of experience doing curatorial and collections work at art museums and non-profit organizations including Hampden Art Study Center, Madden Museum of Art, Denver Botanic Gardens, Colby College Museum of Art, and Arrowmont School of Arts and Crafts. Adams is the 2023-2024 Kenneth R Trapp Craft Assistant/ Curatorial Fellow at Arrowmont School of Arts and Crafts.

Maria Schechter is a bio artist whose work is informed by the natural world she lives in. She works primarily with mycelium in her dimensional paintings and sculptures. She was introduced to sculpture as a child by her grandfather who was a sculptor. In addition, her grandmother’s father was a sculptor of historical significance, Bela Ohmann. His works can be seen as relief on buildings and as sculptures in the round in both Buda and Pest in Budapest, Hungary. Their influence led Maria to pursue her BFA from Cornish College of the Arts in Seattle. She initiated her graduate work at New York University, working towards a master’s in visual arts administration, and later graduated with a master’s in international business and management studies (IBMS) from Schiller International University in Heidelberg, Germany. Maria works primarily with biomaterials, mycelium, tree resin, and foraged botanical materials.

Maria Schechter is a bio artist whose work is informed by the natural world she lives in. She works primarily with mycelium in her dimensional paintings and sculptures. She was introduced to sculpture as a child by her grandfather who was a sculptor. In addition, her grandmother’s father was a sculptor of historical significance, Bela Ohmann. His works can be seen as relief on buildings and as sculptures in the round in both Buda and Pest in Budapest, Hungary. Their influence led Maria to pursue her BFA from Cornish College of the Arts in Seattle. She initiated her graduate work at New York University, working towards a master’s in visual arts administration, and later graduated with a master’s in international business and management studies (IBMS) from Schiller International University in Heidelberg, Germany. Maria works primarily with biomaterials, mycelium, tree resin, and foraged botanical materials.

Schechter has had solo and group exhibits in galleries, museums, and public institutions such as libraries and government chambers. She has received grants from the Goethe Institute New York City, Adolph and Esther Gottlieb Foundation, Schiller International University, Cornish College of the Arts, and UCLA. Maria has founded three significant organizations. The first is the WhatIsArt-WhatIsSound organization, initiated as an arts collective in 1998 with over 200 artists. The organization found its way into 13 countries over a three-year period. Schechter brought it as the primary work to New York University. WhatIsArt-WhatIsSound encompassed 28 cities in 13 countries and earned her a MacArthur Award nomination. The second organization began as a Dadaist type of arts collective in New York, and became the Klaus Gallery and Arts Collective in Brooklyn, NY. She has gained mayoral support from thirteen cities arts and cultural affairs offices including Seattle, Washington, Mostar, (former) Bosnia. Strasbourg, France, and Mannheim, Germany. Her recent work has been showcased with the Minnetrista Museum and Gardens in Muncie, Indiana. She lives in Bloomington, Indiana with her husband and 5 animals.